Fix Your Life with Design Thinking

Fix Your Life with Design Thinking

We spend about 90,000 hours of our lives at work. A place where we learn and refine various procedures and policies to be more efficient in our day-to-day tasks. It seems a waste to not use those learnings to improve our personal lives. For me, a product designer, that means spending a lot of time using a process called Design Thinking. It is a structured approach to problem solving that I have found to be very helpful in tackling aspects of my personal daily tasks.

What is Design Thinking? A Quick overview for those who don’t know.

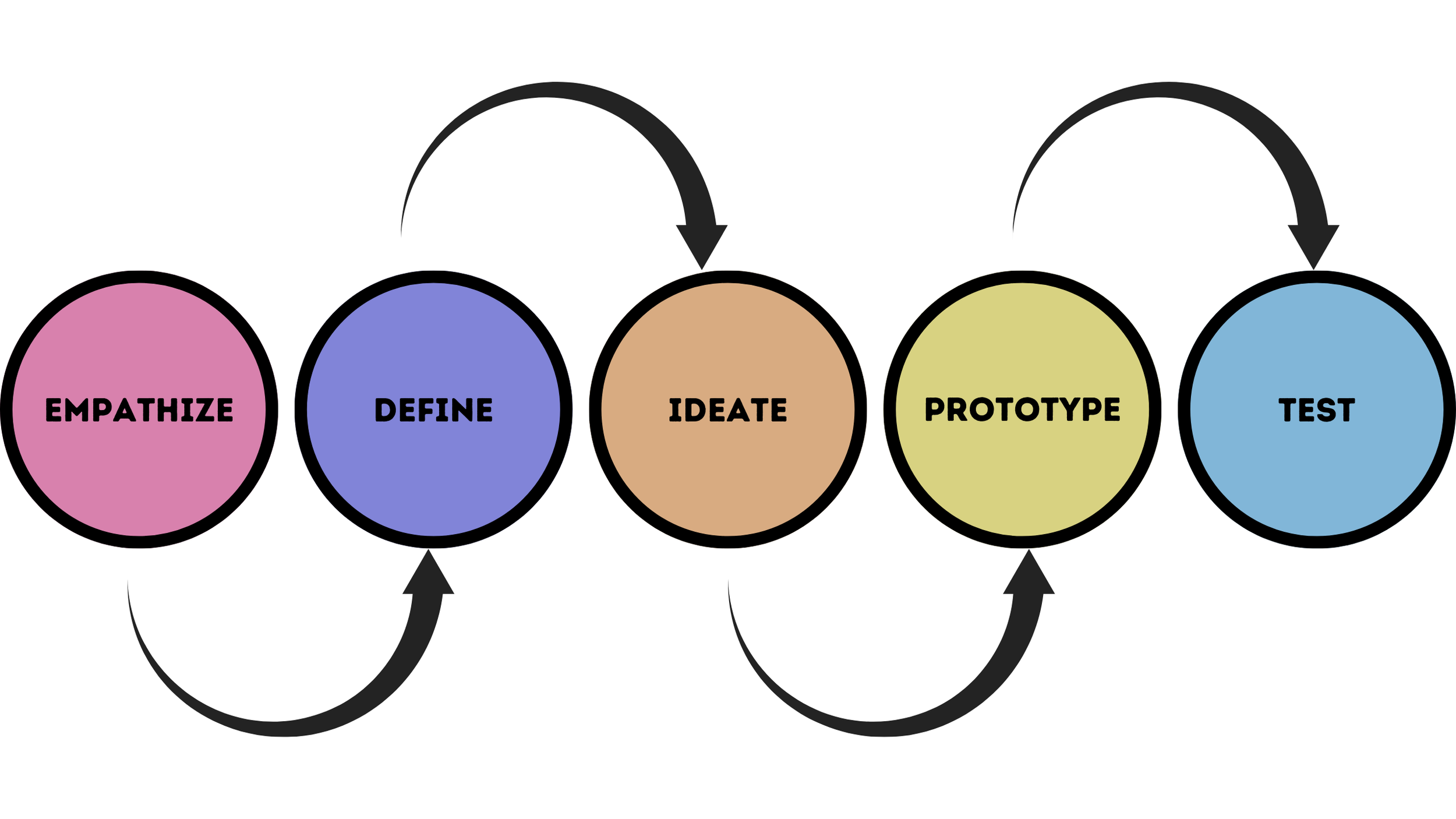

Design Thinking is a step-by-step process to problem solving that goes through five steps – empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test. It helps focus on what the root of the problems may be while allowing flexibility for various solutions. Feedback fuels the process and it can easily be restarted if a specific solution doesn’t work. It is like the scientific theory that we learned in school, but with a focus on iteration and trying new things. This means you can always go back, refine, and restart from any previous step as you learn more.

Design Thinking is made up of 5 steps — Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test

Applying Design Thinking to Everyday Life: Step by Step

Now that you have a very general idea of what Design Thinking is, we must identify how it can support our day to day lives. For this, let’s use an example that I am sure we have all felt at least once: The stress of the morning rush as you start your day.

Empathize

The first step in solving any problem is acknowledging that there is a problem and what the problem is, this happens in the Empathize Step. Here is where we listen and acknowledge that there is a pain point that must be solved. In our example, the pain point is that you don’t like the feeling of being rushed in the morning while you start your day.

We start by listening and observing. How many times do you complain about how hectic your morning was? Did you notice that you have less stress on weekend mornings than weekday mornings? In product design, this is where we would turn to our users, gathering information to better understand what is causing frustration. This step is much easier when we apply it to our own lives. We don’t need to empathize or put ourselves in someone else’s shoes – we already understand our pain point and how it is affecting us. It may sound simple, but problems rarely live in a bubble. Don’t forget to look at the surrounding circumstances too. Here are some key things to look out for:

Identify the users: Who does this problem affect? In our example it might just be you, but if you have a family, they might also affect you and be affected by you.

Identify your constraints: Constraints are your non-negotiable parameters, the things you can’t change and need to factor in. For example, if you have children, you can’t just decide to ignore them in your solution. Does the cat wake you up at an insane hour every morning to be fed? That is another constraint that is more out of your control. Constraints are variables in our design experiment that need to be factored in when making final decisions. Try to think through as best you can, I promise you will discover more as we continue the process.

Discover any baseline data: These will be preliminary and be able to be built upon, but they are great to have for later when you are evaluating the process or looking for possible solutions. For instance, do you get up at the same time every morning? When do you need to complete this process (usually the time you go to work or take the kids to school)? What tasks do you need to get done in that time? This information may also point out possible areas that you want to prioritize when you are thinking of solutions.

The great thing about being your own primary user is that you are the start and end point for this information. You don’t have to go far to figure these things out.

DEFINE

Now that we have determined what the general problem is and its surrounding factors, it is time to narrow things down. There are many factors that might have led to that rushed feeling you get every morning. You may not need to solve all of them, and big changes can often be jarring and lead to lower adoption rates (meaning you are less likely to use your new solution and stick to it).

This is the time to take all that data and information you gathered. We are going to use it to solidify the actionable steps that we can take to solve our morning rush problem.

Look for connections: Do any of the tasks or decisions you need to make relate to each other in some way? Maybe they are all the things you need to do for your children or maybe it revolves around not having what you need when you need it. By putting them in buckets together, you can see patterns that expose the reasons behind your stressful mornings. For this example, we are going to look at some possible reasons you may feel rushed in the morning: you hit the snooze alarm and oversleep, you have to pack lunch and don’t have anything prepped, you forgot about that report that you needed for that meeting today, you have no idea what to wear, you did not sleep well last night and the coffee is not kicking in. Here are some of the groupings using these factors:

Preparation Bucket: packing lunch, choosing an outfit, and knowing what you need for work.

Sleep Quality Bucket: the snooze alarm and not sleeping well.

Must Do Bucket: Tasks with no backup plan, wearing clothes has no other option but buying your lunch can be an alternative to packing one.

Prioritize: Now that you have organized all the information around the problem, you can size up the most logical place to start. People prioritize differently. You might want to start with the easiest path or maybe you want to make the biggest impact right away. There is no wrong answer. Remember, if it doesn’t work, you can always go back to these insights and go down another path.

Pick One: Whatever your logic may be, at the end of the day pick one and focus on that. It will help you focus down and better gauge the outcome of your experiment later. Try to define it as a question to help keep an open mind. Instead of “I am going to prepare everything the night before,” ask yourself “How might I prepare everything the night before?” This will set you up for success in the next step.

The Define stage is all about focus through organization and removing distractions and outliers. It is also where one of my favorite things about Design Thinking really shines – there are no mistakes. By defining your primary question, you have built a reservoir of other potential experiments if the current one doesn’t give you the results you want.

Ideate

Time to put your thinking caps on! Ideation is all about imagining potential solutions to the question we identified in the previous step.

“How might I prepare the night before?”

By having it be a question, you can train your brain to think outside the box. Give it a second and think of potential answers to this question. Here are some of the things I came up with:

Make a checklist to corral smaller tasks so I don’t forget anything

Go over my calendar for tomorrow so I know what I need to prepare

Review my household’s needs for tomorrow to prevent last minute surprises

Do a quick tidy so the mess doesn’t get in my way in the morning

Most importantly, prep and set the coffee maker for automated caffeine

These all have varying degrees of effort and output. Depending on how much you want to try at once, you can pick one or several of them to try at the same time.

If you are having trouble coming up with possible solutions, go back to the data you gathered in previous steps. Specific pain points can be flipped to potential solutions. If one of your pain point buckets focused on the stress caused by last minute requests from your household, then a potential solution is to find a way to prevent those last-minute requests. It might also lead to adding more options to the Define step (see how all the steps interweave with each other).

For our example, let’s go with creating a nightly checklist to act as a reminder for what we need to prepare the night before.

Prototype

We have decided on a solution – woohoo! Now we get to do the thing. That is what the Prototyping step is all about – building out the solution. Don’t put pressure on yourself to get it 100% right. This is one of those “done is better than perfect” situations. There will be time to refine and beautify your solution later as it evolves.

For our example, grab your writing medium of choice (notes app, pen and paper, etc.) and start writing out that nightly to do list. This can be a brain dump, but feel free to start organizing it if the mood strikes. Just don’t let the organization get in the way. Here are a few things to remember about your prototype:

It will not be perfect. It will never be perfect. There will always be something that can make it .01% better. Perfect is not the goal.

New ideas: Solutioning might bring up more issues around the problem you are trying to solve. Add that back to the data you created in the Define stage but try not to let yourself get hung up on it.

Start with the simplest version, you can always build onto it. It will be much harder to adjust a process your brain has decided is already final because it looks nice or already took a great deal of effort.

This step can be the most time intensive depending on the solution that you have chosen to try. It also feels like the most important step because this has been what all the previous steps led to. Personally, this is where doubt starts to creep in for me. Did I choose the right thing? What if I missed something? You are so close to the finish line for this experiment, don’t give up now!

Test

Now is the moment that you get to see how close you came to hitting the mark. You get to take your prototype into the world and see if it makes an impact or not. Now is the time to observe the differences with and without your solution. Objectivity is key here. If you learned something from this potential solution, then you haven’t failed, you’ve simply gathered more insights into the problem. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and there is a good chance your problem can’t be solved in one.

Gauge how much of a total solution you have created. A partial solution can be adapted and adjusted which can save you a lot of time rather than starting at the beginning again. Maybe your list wasn’t organized well, which made your night a bit chaotic, but in the morning you had less to worry about. Minor tweaks are natural, and a good solution leaves room for evolution.

At the same time, the solution might be a bust. Maybe you spent so much time preparing the night before that you didn’t sleep and woke up to a new version of your rushed morning routine. This is the time to have a postmortem on your solution and ask why it didn’t work. These findings turn into constraints when we go back to the Define step. There may have simply been too many things to do in one night, meaning we need to factor that into the next experiment. This is why Design Thinking is so great, you can always go back and try again. A few other things to look out for while you are testing:

Remember to include all the affected parties (for example: your family)

Don’t try to control any factors outside of your current solution, that can skew the outcome.

You might create ripple effects that create new problems, it is important to remember those (your mornings might be easier, but your night is more stressful now).

Write down your findings. I promise you won’t remember everything after a couple of attempts.

If the solution worked and solved the problem in a way that meets your standards, then congratulations! It is time to move onto the next thing that will make your life easier. If the solution you created started to crack later down the line, go back, and see if the components of the problem have changed. Remember, you can always course correct as you learn more.

Phew, that was a lot. With a little practice, it will become second nature. And if it doesn’t work, go back, and ideate on a new solution.

Summary

Design Thinking is a process commonly used in product design, but it is easily applied to personal life problem-solving. It highlights five key steps: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test. The Empathize phase involves acknowledging and understanding the problem, considering personal constraints, and gathering baseline data. The Define phase involves narrowing down the problem and prioritizing actionable steps. Ideate involves brainstorming potential solutions, while Prototype involves building out a solution without aiming for perfection. Finally, the Test phase involves implementing the solution and objectively evaluating its effectiveness, allowing for adjustments and iterations as needed. Through these steps, Design Thinking offers a structured approach to addressing personal challenges and improving daily routines.